Mass Timber in Single-Family Homes (2024)

By Emily Dawson, AIA, LEED AP Architect | Owner, Single Widget

Overcoming the paradigm of site-built, light frame housing in the $570B construction sector

I recently spoke to a market analyst who said something that made my jaw drop. Consultant Tim Seims has worked for decades in both the US and Japan introducing new construction products to risk-averse markets. He told me, “No product category has hit mass-market adoption without getting into single-family residential.” I could hardly believe my ears, having spent most of my own career in commercial construction. But his declaration validated my growing sense over the past few years investigating manufacturing and mass timber housing—this sector holds important feedback for bringing mass timber into the mainstream. After all, it is a very nice scale to prototype new ideas. If what he says is even partially true, anyone trying to scale a structural timber business would be remiss to ignore the country’s largest construction sector.1

Getting mass timber into single-family homes has clear advantages to the homeowner over its main competitor, light framing. The resulting structure is higher-quality and has an increased ability to protect the occupants and recover from events like fires and earthquakes. This security equates to real value, especially if we consider lenders’ and insurers’ mounting concerns about asset resilience in the face of increasingly frequent climate disasters. Other benefits include an environmental carbon and forest management story; new timber markets that use fiber from forest thinning projects could help sustain the forest management needed to create resilience on the landscape, and in turn, store carbon in durable structural products. But standing squarely in the way of swift adoption are the multi headed challenges of uneven regulations across jurisdictions, high material costs, and the inertia of ingrained light frame construction methods.

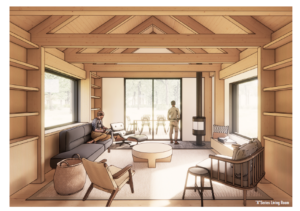

WHILE THEY VALIDATE THEIR MARKET, GREEN CANOPY NODE PARTNERS WITH A FABRICATION CONTRACTOR TO REDUCE OVERHEAD. THIS ALLOWS THE COMPANY TO FOCUS ON PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND SCALE SUSTAINABLY AS THEY BUILD REVENUE.

Source: Green Canopy NODE

Credit: J. Craig Swea

Cost aside for the moment, could higher-quality buildings be enough to tip the scales? Timber Age Systems2 founder Kyle Hanson shares a concern about the durability of light frame buildings with MOD X3 founding partner Ivan Rupnik, though they come at the problem from different angles. Hanson says he is dismayed by the overall quality of housing in Durango, Colorado, an opinion he formed after years of working in real estate. He believes that high-quality mass timber homes will be an essential part of creating lasting financial security in his community. From a fabrication standpoint, Rupnik notes that the stability of most softwood lumber produced today does not integrate well with manufacturing assembly lines, which require material precision to run smoothly. Indeed, modular timber manufacturers across Europe, where the baseline construction analogues are sturdier than in the US, wouldn’t dream of framing with feisty dimension lumber. They reach for a shelf-stable laminated veneer product like Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL).4

Hanson and Rupnik both point to one promising answer to two major problems: the nation’s housing crisis, and the need to cut emissions in the carbon-intensive construction industry. It could lie in an industry wide shift from site-built to off-site construction.

Let’s turn our attention back to cost competitiveness. We know that replacing concrete with solid wood often works for multifamily buildings, but for mass timber to compete with light framing, a major shift in thinking is required. Start-ups across the country are counting on off-site fabrication to find an advantage over light framing’s site-based vulnerabilities. The high material cost of mass timber, in many ways, is driving the need for multitrade modular solutions as a way to enter the market by moving the most time-consuming and riskiest parts of construction under cover.

MARKET RATE OFFERINGS WILL MAKE UP THE MAJORITY OF THE PANELIZED CLT HOMES TIMBER AGE

FABRICATES, WITH CONSISTENT DELIVERY OF A SMALLER NUMBER OF LUXURY PRODUCTS.

Source: Timber Age Systems

Weather-related schedule delays, unreliable access to labor, safety hazards, sequencing clashes, road closure fees, and delayed inspections are all common reasons on-site construction requires such high contingencies. In a factory setting, scheduled interactions under controlled, ergonomic conditions prevail, ideally creating a construction process that is predictable enough to allow everyone to take contingencies way down. The hurdles new modular companies face when proving their products in established markets are high. For developers to confidently agree to move costs from a site to a factory, they need to see precedents that clearly demonstrate the value; but, at this point, the approach is still relatively uncommon. And of course, it is a much more difficult sale if the product costs even a little bit more overall than the standard approach.

Even in commercial construction, mass timber is a high cost-per-square-foot item. Residential builders working with commercial-grade products have a harder time making it pencil. Trent Debth is an energetic entrepreneur out of Dallas who says his company’s5 most significant pain point is the cost of mass timber panels. His team decided on a kit-of-parts Mass Plywood Panel (MPP) solution that they could fine-tune to a greater degree than working with full panels, which were overbuilt for their designs. Vermont-based Mass Kingdom’s Josh Oakley landed on a similar strategy with Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT), noting the advantage to his rural customers of being able to move kit parts on-site by hand.

What if single-family homebuilders had access to panels optimized for lower structural loads, and tested under lighter requirements? CLT panels made with thinner lamstock would reduce unnecessary fiber and cost. Veneer-based panels are available in increments of 1-inch thicknesses, but they could be configured more finely if the market proves ready.

MASS KINGDOM’S KIT-OF-PARTS SYSTEM CAN BE CONFIGURED IN ENDLESS WAYS AND INSTALLED WITHOUT HEAVY MACHINERY.

Source: Mass Kingdom

Some mass timber manufacturers are responding to customers asking for a new kind of product with specialty runs of prototypical thin panels. But it is still a chicken-and-egg situation. To grow a modular mass timber single-family market, builders need a robust array of light-duty offerings focused on noncommercial uses, and manufacturers need compelling reasons to invest in developing these products.

If the only challenge was the bottom line, one could imagine these thinner mass timber products entering the established prefab home ecosystem, validating the market (or not), and we could move on. Unfortunately, whatever the structural material of choice, all modular companies face a daunting regulatory reality. Gary Fleisher has worked in the modular industry for decades and says that the largest biggest detriment to modular housing is the vast variation in code adoption across the country.

A modular enterprise is a big-ticket item, and the larger the potential region for sales, the better. State-by-state inconsistencies impede interstate commerce, and local officials wreak even more uncertainty city by city. When inspection requirements change frequently and vary significantly across borders, the investment risk for modular companies mounts. A small change can translate into a huge expense on a production line. Product cost goes up and competitiveness goes down as a result. When code changes and adoption cycles are not triangulated with the broader goals of, say, creating more housing or industry efficiency, they can hold back innovation.

Code creators are interested in industrialization. ICC6 and HUD7 are both aware of their roles in clearing barriers, and they have been making regulatory progress to encourage more factory-built construction. But these regulations mean little until they are adopted. That onus rests on state governance; it may take a few years in one jurisdiction and decades in another. Without consistent, collaborative feedback cycles and adoption, innovators are stuck focusing on smaller market regions and constant change management. If code creation and adoption were more strategic and consistent across the country, would we see an increase in industrialized construction? Could regional or national cohorts of modular companies help promote innovation?

The mass timber modular housing start-ups operating today are trying to build for the future in a world still living in the past. Will they succeed? On their side is the uneasy reality that we are living in a time of great change. A nationwide housing crisis is colliding with increasingly destructive climate-related disasters. In our search for solutions to these problems, we find answers in our forests, and, in their endlessly enlightening ways, our forests beseech us back. Wouldn’t it be a magnificently balanced case if the buildings we need the most help us serve our landscapes better? To move mass timber single-family housing from niche to norm will require collaboration, and maybe a little risk-taking, from a huge range of industry professionals—from the natural resource to the completed home.

The potential rewards are, well, jaw-dropping. If it works, the gigantic scale of the resulting market would be a boon to expanding mass timber manufacturing. Innovators already working in this sector are confronting these barriers with some successes, but it will take a broadly coordinated effort from many players across the industry to truly lower the hurdles. If the result is a new standard for beautiful, high-quality homes that help our forests, it will certainly be worth the trouble.

1 According to US Census Bureau data, the modest yet proliferating single-family home represents almost two-thirds of all residential construction, and nearly one-third of all construction dollars (2022

2 Timber Age Systems is a mass timber housing company based in Durango, Colorado.

3 MOD X is a global strategy advisory group in the prefabricated and volumetric modular off-site construction industry.

4 The advantage of LVL, like many other mass timber products, is its dimensional stability through shifts in humidity and temperature, which are unavoidable during transport, fabrication, and installation.

5 TimberBLDR

6 International Code Council (ICC), ICC/MBI Standards for Off-Site Construction 1200-2021 (Planning, Design, Fabrication, and Assembly) and 1205-2021 (Inspection and Regulatory Compliance).

7 MOD X for US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Offsite Construction for Housing: Research Roadmap (2023).

Download PDF

View the Agenda

View the Agenda

Book a Building Tour

Book a Building Tour

Book Your Exhibit Space

Book Your Exhibit Space

Explore the Exhibit Hall

Explore the Exhibit Hall

Become a Sponsor

Become a Sponsor

View Sponsors & Partners

View Sponsors & Partners

Reserve Hotel Rooms

Reserve Hotel Rooms

Discounted Plane Tickets

Discounted Plane Tickets

Read Case Studies

Read Case Studies

Download Past Reports

Download Past Reports